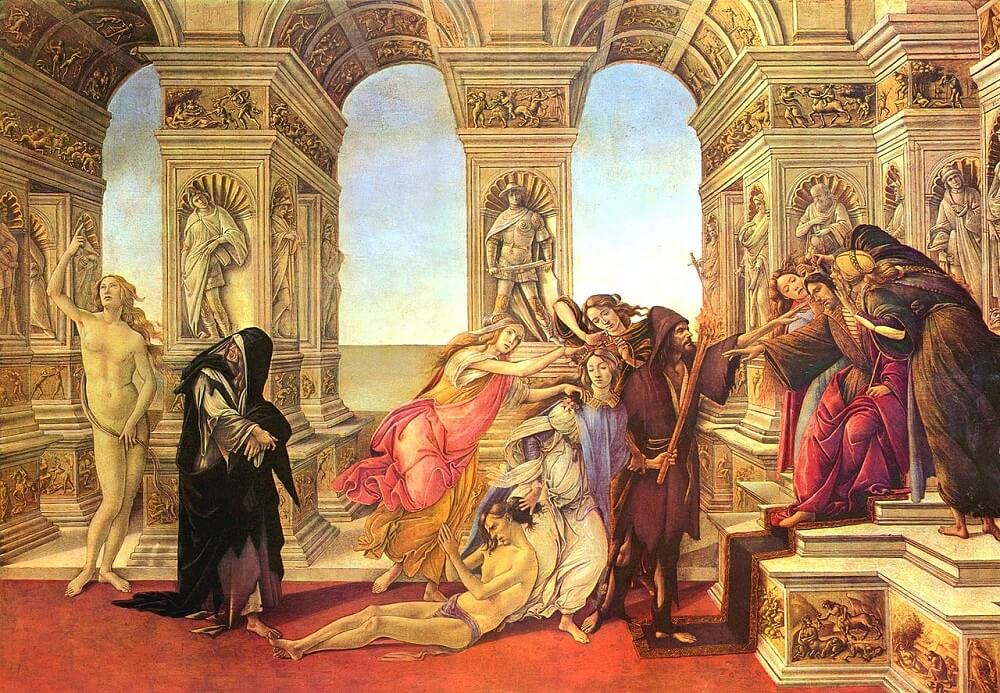

Calumny of Apelles, 1494 by Sandro Botticelli

The last painting in which Botticelli was to take a secular story as his subject is The Calumny ofApelles. The observer is surprised both by its relatively small size - a mere 62 x 91 cm - and by the miniature-like fine painting technique. These two factors lead to the assumption that this picture - like the panels of twenty years before depicting the story of Judith - was intended not as a wall decoration or as an ornamentation for a piece of furniture but rather as a particularly precious and treasured object, inviting the observer to examine it closely. The portrayal recreates a lost picture by Apelles, the famous classical painter, known to us solely through its description by the poet Lucian in his "Dialogues".

Lucian tells us that the painter Antiphilos, driven by envy of his far more talented colleague Apelles, accused him of being involved in a conspiracy against the Egyptian king Ptolemy IV, at whose court both artists were engaged. The innocent Apelles was thrown into prison, until one of the real conspirators testified to his innocence. Ptolemy rehabilitated the painter by giving him Antiphilos as his slave. Apelles, still filled with horror at the injustice that had been done him, painted the afore-mentioned picture, in which the calumny against him was presented in allegorical manner, as may be seen in similar form in Botticelli's painting.

The king is sitting on the right-hand side of the picture on a raised throne in an open hall decorated with reliefs and sculptures. He is flanked by the allegorical figures of Ignorance and Suspicion, who are eagerly whispering the rumours in his donkey's ears, the latter to be understood as symbolizing his rash and foolish nature. His eyes are lowered, so that he is unable to see what is happening; he is stretching out his hand searchingly towards Rancour, who is standing before him. This latter, clothed in black, has fixed the King with a piercing look and is stretching out his arm with its overlong hand towards him in a sharp, aggressive gesture. With his right hand he is dragging Calumny forward; as a symbol of the lies which she has spread, she is holding a burning torch in her left hand, while she is pulling her victim, an almost naked youth, by the hair behind her with her right hand. His innocence is shown by his nakedness, signifying that he has nothing to hide. In vain has he folded his hands so as to beseech his deliverance. Behind Calumny, the figures of Fraud and Perfidy are studiously engaged in hypocritically braiding the hair of their mistress with a white ribbon and strewing roses over her head and shoulders. In the deceitful forms of beautiful young women, they are making insidious use of the symbols of purity and innocence to adorn the lies of Calumny. At some distance follows Remorse, an old woman dressed in a torn black gown; her mouth twisted with bitterness, she is turning to look at the final figure, Truth, standing at the edge of the picture. This latter appears like the statue of a classical goddess, reminiscent of Botticelli's The Birth of Venus. A naked woman whose beauty is quite perfect, she is pointing upwards with the index finger of her left hand in the direction of those powers from whom the Last Judgement regarding truth and falsehood can be expected. She is paying no attention to the doings of the others, who are all making for the king, and is thereby completely isolated from them; as such, she is manifesting her incorruptibility and immutability. Her nakedness links her with the blameless youth, while the other figures have hidden their true nature under their clothing. Rancour and Remorse frame Calumny and her comrades, representing the cause and consequence of the betrayal. Botticelli has made it clear that they belong together through their black garments, which set them apart from the bright clothing of the other figures.